How America Abandoned Its Iraqi Interpreters

5/6/2018 5:51:00 PM

5/6/2018 5:51:00 PM

4879 View

Dr. Amy L. Beam

+

-

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq to topple the dictator, Saddam Hussein. They thought it would be a quick victory. In December 2011, the US finally left Iraq . . . in ruins and sectarian warfare. During those years of occupation, tens of thousands of Iraqi citizens risked their lives working as interpreters for the US military on the frontlines, and guiding American soldiers and commanders through Iraqi politics, tribal disputes and social customs. The US government never accounted for how many Iraqi interpreters were hired, killed, or injured in spite of being ordered by Congress to produce the numbers.

Many were Yezidis. Hundreds died in action and thousands were wounded. After British forces pulled out of Basra, the southern Iraqi port city, interpreters were rounded up and slaughtered en masse. After the US left in 2011, many others were targeted and killed for working with the US. In 2007, the US Congress created the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program and the P2 program to allow interpreters from Iraq and Afghanistan whose lives were at risk to immigrate to the US with their families and become lawful permanent residents (LPRs) upon entry.

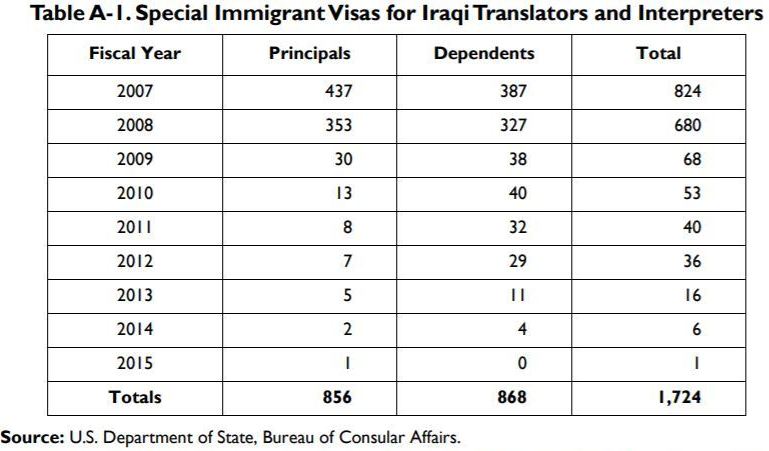

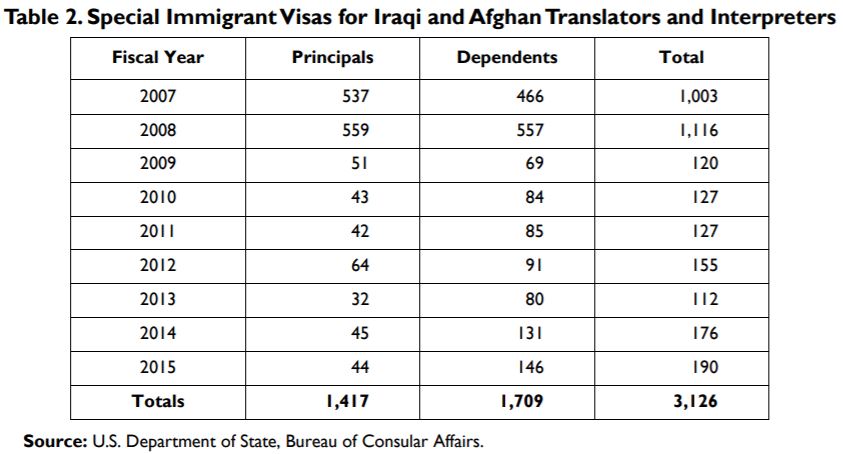

The SIV program was for interpreters and translators who had worked at least one year for the US Armed Forces between 2003-2011. Beginning in 2008, Congress expanded the SIV program to accept 25,000 interpreters and their families over five years. Yet for fiscal years 2008 through 2012, only 1,645 applicants and their dependents were resettled in the US. That amounted to just over 6% of the allocated number of 25,000. The process was so bureaucratic and difficult that it was virtually impossible for any interpreter to complete his documentation process with IOM without English-speaking legal assistance.

Applicant processing for the SIV program came nearly to a halt in 2010. In the next six years only 36 Iraqi interpreters were admitted to the US. The ratio of dependents to applicants was approximately one-to-one, meaning the interpreter brought his wife, but not other family members. Since Iraqi families are typically large, this meant painful family separation from their loved ones.

A State Department email leaked by Wikileaks advised that interpreters should not be brought to the US because there might not be enough remaining in Iraq and Afghanistan when the US decided to return.

State Department memos leaked by Wikileaks confirmed the delay in processing interpreters' applications. On July 12, 2011, Eric P. Schwartz, Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (BPR) sent an email to Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, in which he stated, "The NY Times will publish a story tomorrow that describes delays in US refugee and SIV resettlement processing from inside Iraq, and correctly notes that individuals have thus been subjected to substantially increased risks of persecution as they've awaited USG (United States Government) permission to depart. . . . The delays are real, and result from new DHS security screening procedures that involve the intelligence communities. . . . the additional procedures have indeed slowed the process, causing delays of many months or longer. Second, the cases of a higher number of Iraqis are being put on 'hold' due to security information that raises questions about the applicant's suitability, and the intelligence community has not devoted the resources that would be necessary to quickly resolve, one way or the other, the status of these holds."

In spite of Eric Swartz's statement of delays of months and that not enough resources had been devoted to the security screening, the Department of Homeland Security indicated in response to a question following the October 2011 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that it did not need additional resources to expedite SIV petition processing. At a December 2012 House Homeland Security Committee hearing DHS testified that it takes between three and ten days, on average, to process an Iraqi or Afghan SIV petition.

The statement of three to ten days to process an SIV application can only be viewed as a blatant distortion of the facts to Congressional inquiries. Many SIV applicants waited between one and eight years for IOM to process their applications before being scheduled for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) interview. Many others who completed their interview with DHS and completed their medical exams were never called to fly to the US before their medicals expired six months later. When and if they were finally called, they had to repeat their medical exams.

Those who applied in Ankara, Turkey, in 2014 and 2015, then later returned back to Iraq when the Turkish refugee camps were closed, had to return to Ankara to complete their interviews and medicals. However, in 2016, Turkey stopped issuing visas to Iraqi citizens. I personally met with the Iraqi Vice Councilor in Erbil Turkish Embassy to obtain visas for six Yezidi families to return to Ankara for their interviews and medicals. In addition to the requirement to return to Ankara from Turkey, when the families were finally told their visas were approved, they were required to send their passports to the US Embassy Ankara using the Turkish post office and, also, to receive them back by the Turkish post office. Each passport holder had to appear in person both to send his or her passport and to receive it back with the US visa stamp. This was an impossibility, because they could not obtain visas to Turkey.

It took the US Embassy in Ankara one year to transfer their cases to Baghdad for interviews. Traveling ten hours by car from Kurdistan to Baghdad for two interviews with IOM and DHS cost a family $500 US dollars for each trip, including driver, hotel, and food. Few families had this money, so many had to cancel their interviews. If the interpreter asked for his interview to be transferred from Baghdad to Erbil, he was not told that it would never be scheduled. The Embassy could not transfer the DHS interview process to Erbil, Kurdistan (three hours from the IDP camps), because all Embassy staff are required to live and sleep inside the Embassy or Consulate compound. The US Consulate in Erbil did not have enough beds for the DHS staff, thus DHS interviews could not be conducted in Erbil.

The SIV program ended to new applicants September 30, 2014. The number of visas after that date was limited by Congress to 2,500 at a rate of only fifty interpreters per year. In 2015, only 190 interpreters and dependents from Iraq and Afghanistan were resettled in the US. By 2018, some applicants were still waiting to be processed.

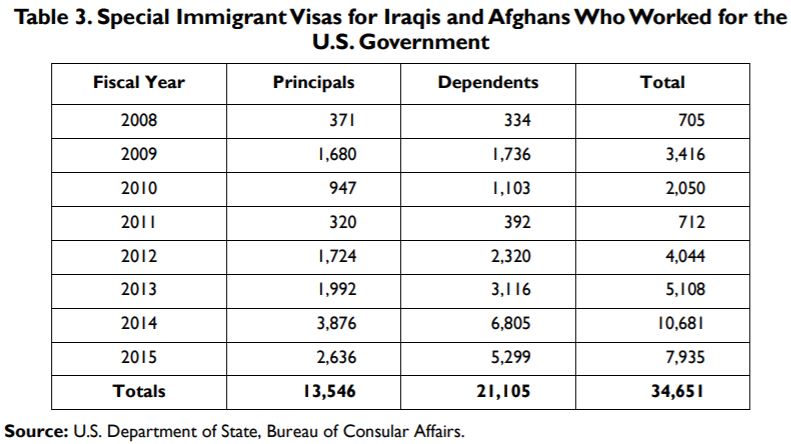

The P2 program was also created by the US Congress in 2007. It has no expiration date. It applies to anyone who worked at least one day for the US government or a US company in Iraq between 2003-2013. Tens of thousands of applicants have been waiting years to be processed.

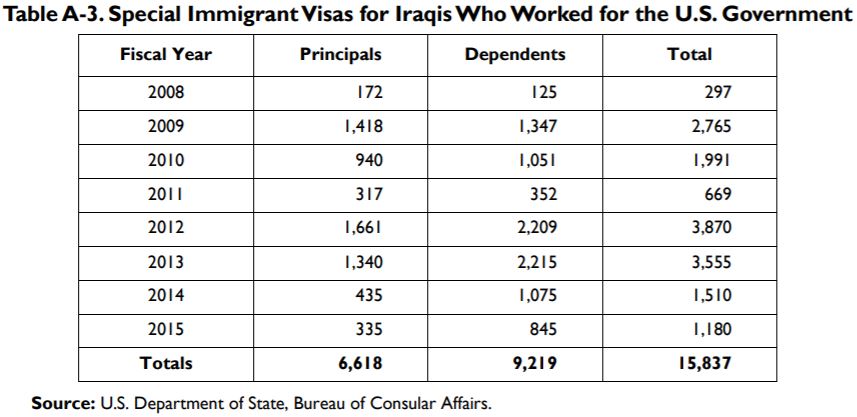

From FY2008 through FY2015, 37,777 Iraqi and Afghan nationals had been issued SIV (3,126) or P2 (34,651) visas to the United States. Principal applicants accounted for just under 15,000 of the total; the others were dependent spouses and children. This ratio indicates tremendous suffering caused by family separation. Many eligible family members have been waiting more than ten years in Iraq to join their immediate family members in the US. This means many parents in Iraq may never again see their sons, daughters, or grandchildren. In 2017, President Trump referred to the immigration policy which allows family reunification as "chain migration" and vowed to end it.

Priority is given to (1) medical emergencies, (2) persons with protection concerns, and (3) Yezidis. Priority is also given for (4) humanitarian exceptions for including ineligible family members who cannot be left behind, such as an elderly widowed mother-in-law or a young single woman over age eighteen. In Baghdad, I met a widow whose husband was killed in battle and whose three sons worked as interpreters. All three received credible threats to their lives. Early in the SIV program, they were resettled in the US. In spite of the priority given to "humanitarian exceptions," their elderly mother has been waiting ten years to join them and see her grandchildren. They are not safe to return to Iraq for a visit.

The International Office for Migration's (IOM) role is to collect the required documents and conduct the first interview with the family members. When their documents are all collected, the case is referred to the US Department of Homeland Security, Citizen Information Services (CIS). A team comes to Baghdad several times a year to interview applicants. Those who are approved are then handled by IOM again which provides air transportation to the US. IOM does not make selection decisions.

I got involved with helping interpreters with their applications to IOM in 2016. They could not get the required letters of employment verification from their US employer, Global Linguistics Systems (GLS). GLS had posted many stories on the internet stating that the company had gone out of business after the US withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 and "shredded" its employment files for interpreters. What nonsense to talk about shredding paper files in the electronic age.

It took my lawyer friend 24 hours to track down the Vice President of Operations for GLS. It took the V.P. ten minutes to verify employment of one of my cases. The employment that GLS had on record was 18 months longer than the period for which the interpreter had been paid as a GLS employee. I understood immediately that GLS had overbilled the US government for the interpreters, probably to the tune of millions of dollars. Thus, the company owners wanted everyone to believe they had gone out of business.

I sent some emails out to some US embassies, consulates, and GLS threatening to report GLS for fraud if they did not immediately send the letters of employment verification to the interpreters who had been trying to get them for two years. GLS could risk sending the letters which documented overbilling or risk having me report them to the Government Accounting Office and Congress for fraud.

Miraculously, within two weeks, the letters of employment verification began arriving by email to the interpreters who had waited up to two years for them. Five interpreters shared their letters with me in one week. All of their letters documented employment from six months to two years longer than they had actually been employed. For one year we were able to get these letters from a helpful GLS employee, often within hours, until the GLS staff position was eliminated.

The IOM process was so back-logged that by the time IOM had collected all the interpreter's documents, the letter of employment verification was more than one year old. Because of IOM's inefficiency, the interpreter was penalized and was once again required to get a new letter. Most of the Army commanders and supervisors of the interpreters were retired or dead. For many interpreters their applications were not processed due to this problem.

When Donald Trump became US President in 2017, he immediately issued an executive order banning immigration from seven Muslim countries, including Iraq. Some interpreters' families had already been approved and issued visas to travel. They had sold all of their belongings and then were denied entry to the US. Others were already en route to the US and were flown back to Iraq. In response to an angry outcry, the Trump administration amended its visa ban to allow immigration by the families of Iraqi interpreters who had served the United States government. Yet, in reality, very few Iraqi interpreters were resettled in the US after the ban.

SIV and P2 immigration was suspended until September 30, 2017, as the ban worked its way to the US Supreme Court which overturned the bans based on unconstitutional discrimination. Trump went back to the drawing board and issued even more onerous immigration bans. Although Iraq was removed from the list of banned countries, immigration remained halted.

The week of the Supreme Court ruling, many interpreters received form letters stating their scheduled interviews were canceled due to "technical difficulties." Others received notice that their applications were denied because they were deemed to be "security risks." No evidence was provided. There was no appeal process. One case included the doctor in Duhok who had cared for me for free after my car accident in 2016.

An earlier denial was for an interpreter nicknamed Matt. He was denied a visa despite submitting a dozen letters of recommendation from American officers. One letter said he had not only saved American soldiers from a burning Humvee, and treated the wounded, but that he had been abducted in 2007 by a local militia and interrogated about working for the Americans. He was denied a visa and never told why.

By late 2017, refugee resettlement from Iraq to the US had come to a virtual stand-still. During the four-month period from December 1, 2017, through March 31, 2018, only thirty Iraqis applicants and dependents were issued visas and resettled in the US under the P2 program and 206 under the SIV program. In spite of a backlog of tens of thousands of applications, when I got a tour on April 5, 2018 of the center inside the Baghdad US Embassy where interviews are conducted, it was empty except for a mother with two children.

The Embassy was waiting for policy direction from Washington, but the slow-down was the handwriting on the wall. The Trump Administration was not interested in accepting immigrants. Those Iraqi interpreters who had risked their lives for Americans were abandoned, living in tents with no home to return to and no escape from Iraq. Daesh had exploded the houses of anyone who had worked for the US Army. The interpreters felt bitterly betrayed. Their lives will always be in danger living in Iraq.

On April 26, 2018, IOM conducted interviews in Baghdad with approximately 40 Yezidi interpreters and their families. Hopefully, their Homeland Security interview will be soon and they will be in the US before the end of 2018.

Immigration arrival statistics are public information at:

https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43725.pdf

http://www.wrapsnet.org/admissions-and-arrivals/

Dr. Amy L. Beam is author of the book "The Last Yezidi Genocide," soon to be released in English, Arabic, and German. She has helped and advocated for the Yezidis since ISIS attacked them in August 2014 in Shingal, northern Iraq. Follow her on FaceBook. CONTACT: amybeam@yahoo.com.