The Yezidi Crisis Worsens: No Escape, No Return

8/7/2018 5:02:26 PM

8/7/2018 5:02:26 PM

4056 View

Dr. Amy L. Beam

+

-

Nearly four years after the Islamic State attacked Yezidis in Shingal, northern Iraq, in August 2014, their biggest problem is hopelessness and profound disappointment in humanity. They can neither get asylum nor return to their homes in Shingal. A twenty-year old girl told me, "I don't know why I am living. I am just waiting to die."

Two hundred thousand Yezidis live in tents and caravans in camps in Kurdistan and another 100,000 live outside the camps, many in unfinished buildings. They no longer get basic supplies given to them like shampoo or cooking oil. Their tents are rotting. In the last week, tent fires occurred in Khanke and Jamishko camps, killing one teenage girl. When electricity goes out for hours, there is no air conditioning in the 45C heat.

Only Australia is currently offering asylum to a few families of survivors who escaped from ISIS captivity and rape. Those who were not captured by ISIS have little hope of qualifying for any asylum program. Smuggling to Europe has come nearly to a halt because of tighter controls at the Bulgarian border and Turkish water route to Greece. Even paying a bribe for a Shengan visa has largely stopped. Legal immigration for interpreters who served with the US military has also nearly stopped in spite of the priority given to Yezidis. European countries are threatening to return asylum seekers to Iraq.

Yezidis do not want to return to their homes in Shingal without international protection or military backing of their own Yezidi Hashd al Sha'abi forces. According to an eye-witness traveling to Mosul, on June 1, a convoy of 24 Coalition vehicles and one Iraqi Army vehicle entered Shingal from the road from Tal Afar, 23 kilometers east of Shingal cement factory. Kurdistan24 news site quoted the assistant mayor of Sinjar city as saying the Americans were planning to build a base on the summit of Shingal Mountain, but on June 3, some Yezidis who traveled there found no military presence and only a few Yezidis there.

In an interview with General Najim al-Jubouri, Commander of Nineveh security, on May 20, he stated that in the very near future the border between Iraq and Syria would be secured. This military convoy may have been headed to that border at the west end of Shingal Mountain. This is where Yezidis walked off the mountain to Syria on August 12, 2014, after Coalition airstrikes and PKK opened a corridor for the besieged Yezidis.

On May 27, 2018, I drove around the west end of the mountain with my Ezidi Hashd al Sha'abi driver and armed guard, assigned by Ezidi commander Khal Ali in Sinjar city. The road was deserted except for two Iraqi Army checkpoints. The checkpoint where Shiloh Road turns north and Highway 47 continues straight west to the Syrian border was guarded by Iraqi Army soldiers who asked questions and checked everyone's ID without smiling or banter. A single, American woman, not in uniform, was a curious event, but they accepted my written permission from General Najim, head of Nineveh security, to go anywhere in Shingal.

We turned north on Shiloh Road. Three times we had to drive on the dry gravel culvert where bridges in the road had been destroyed. One time we passed three large water trucks coming from the fresh water spring in Barre. Their destination was the Ezidis living in tents on top of the mountain.

In Barre about thirty families (or maybe it was people) have returned. We found Hassan Shervan tending about 300 black goats. His father and brother were killed by ISIS in 2014 in Eskeenia. We were unable to visit Eskeenia on the southwest side because it has a PKK check point. I am sure I would have been welcomed, but protocol requires that Hashd al Sha'abi not meet with PKK.

The last Iraqi Army checkpoint heading north around the western end of the mountain was guarded by a young Iraqi Army soldier who used to wear a YPG uniform. My driver pointed to a house on the left and said, "That is Syria." On our right was Iraq. It was wide-open, empty land, with no one in sight, but safety can be an illusion. There were no fences to indicate the border. ISIS is still active in Syria. Without a fence or markers or at least a military patrol, it appears that anyone can walk over the border from Syria to Iraq. The Kurds, divided between Rojava, Syria and Kurdistan, Iraq, do not want to be divided by a border fence, but Yezidis do not want to be vulnerable to another ISIS attack. On the other hand, they are buying food from Syria because the road from Zakho, Kurdistan remains closed.

The Ezidis want to control their own lands. With gratitude to all who helped them, PKK, YPG, YPJ, the Iraqi Army, and even the Shia and Sunni Hashd al Sha'abi units under the Iraqi Ministry of Defense, the Ezidi Hashd al Sha'abi want to be in control of the check points, especially the four entry roads to Sinjar city. Outsiders do not know the region nor the Kurdish language and cannot identify potential ISIS members or outsiders.

The golden light of the setting sun was awesome, the backlit red poppies brilliant, the black goats at Barre were coming home for the night. We stopped for photos. I missed my tourism business in Turkey and imagined bringing tourists to hike around in the beauty of Shingal Mountain. But that is a fantasy that can never come to fruition. Even thirty years after Saddam Hussein's campaign of terror, hundreds of old villages cannot be entered because of unexploded bombs.

Shingal is strewn with thousands of unexploded bombs. When ISIS left, they wired many houses with explosives. It is not safe to return to any of the two dozen villages south of Shingal Mountain. They have not been demined. Even Sinjar city, with a returned population of 10,000, is dangerous. Those who returned have hired someone to check their house and remove the explosives, while others just took their chances.

• In January 2018, children found three unexploded bombs in the Sinjar Hospital.

• In April 2018, four men were killed in two different explosions in Gir Zerik. Three were Iraqi police. The other was the watch tower guard.

• Two shepherds died by explosives near Tal Banat in 2018.

• Two Iraqi Army men were seriously injured when a house exploded in Siba Sheikh Khudir in April 2018.

In Sinjar city, some Yezidi survivors who returned from ISIS captivity are living in Sunni houses which they cleaned themselves. There are no spaces for them in camps in Kurdistan. The Shia houses remain empty under the assumption that Shia Arabs will return sooner than the Sunni Arabs. Yezidis feel the Sunnis will not return for a long time, because ISIS was primarily composed of Sunnis.

Between May 22-26, 2018, I visited the following villages: Sinjar city, Kocho, Hatamia, Qapousi, Tal Qassab, Tal Qassab Kevan, Tal Banat, Hamadan, Nuseria, Solagh Institute, Ain Gazel, Domis, Siba Mahmood Khero farm, Siba Shaikh Khudir, Tal Ezeer, Gir Zerick, Eskeenia, Barre, Khanasor, Snoni, and Borik.

All the Ezidi villages on the south side are empty except for Sinjar, Tal Qassab, and Tal Qassab Kevan. There are check points at the entrance to most of the empty villages to keep people from driving or walking where it is dangerous.

Kocho, where the men were killed and all the women and children were captured August 15, 2014, is guarded by six Kocho survivors, including Khalid Murad Pissee, brother of Nadia and Said Murad. They are guarding the bones and vow to stay for as long as it takes for a team to show up and excavate the grave sites or else build a Yezidi shrine as a memorial.

Inside Kocho school the walls are filled with photos of over 600 persons who were massacred. When I looked at his six brothers, including Khairi, the husband of Muna who is in my Facebook profile photo, I commented, "Oh, these are your six brothers who were killed." Khalid answered, "They were all my brothers."

The wall of older women who were killed at Solagh Institute really crushed me. I have listed nearly every one of these women as missing or dead in my letters to the Duhok Director of Passports when I got passports for their children who escaped ISIS. So if someone wants to take on a project, please bring a team of forensic specialists to excavate and identify the bones so these men can be freed from their vigil.

Khalid and his team have identified ten execution sites. He walked me in the field which is strewn with long bones.

At the western end of Shingal, another massacre of huge proportion occurred. In Siba Sheikh Khudir one of the Ezidi guards showed me his house that exploded in April severely injuring two Iraqi Army soldiers who triggered an IED when they entered the house. The owner told me that on August 3, 2014, he witnessed all 200 Peshmerga gather together at the police station on the hilltop overlooking his house. At 1 AM in the morning they left. At 2:30 AM Siba Sheikh Khudir was attacked by ISIS. Grave sites throughout the town contain 600 bodies including women and children. The men fought until they ran out of ammunition at 7 AM.

There is no electricity in the villages. ISIS removed all the cables from the utility poles between Siba Sheikh Khudir, Tal Ezeer, and Gir Zerik. The electrical power station near Siba Sheikh Khudir is damaged and unusable.

There is no water source in the villages. In addition, the electrical wires and fixtures and the plumbing fixtures have been torn out of many houses and sold.

Between 30% to 60% of all buildings and marketplaces in the villages are damaged or totally destroyed. Many houses were burned to a black crisp on the inside, and the plaster is cracked and falling off.

Nearly all stoves, refrigerators, and washing machines were stolen by ISIS and sold in open air markets in 2014. Furnishings were stolen by anyone and everyone after Sinjar city and the villages were cleaned of ISIS. By the time security check points prohibited removing furniture from Shingal, most furniture had been stolen and taken to Duhok.

All doors and windows are removed or broken. In Sinjar city, Naim Ali has been building new doors and windows and repairing old ones and installing them for returning occupants for more than two years. His workshop is across the street from the new playground in Sinjar, at the round-about. He also cuts glass for windows. Two years ago, we were the only people living in this neighborhood. Now the street is lined with vendors selling food, dry goods, and clothing. One man was opening a printing service and book store. The playground was full with about 20 children.

West of Sinjar city I visited the farmhouse of Barakat Mahmood Khero at the junction to Tal Ezeer, six kilometers to the south. That road is now closed. The farm house was guarded by Iraqi Army soldiers who spoke Arabic, but no Kurdish. The commander argued emphatically that I could not cross the dirt berm, approach the house, or photograph. I argued just as vehemently that I DID have permission and he was not going to stop me. My permission was signed by General Najim. He finally relented with two conditions: I had to be sure not to include any of his soldiers in the photos and not to include the Iraqi flag. I found this curious not to include the flag until mulling it over.

The wife and children of Barakat Mahmood Khero who was shot and killed on his property with 12 men lives in a tent in Kurdistan. This farm house and expansive acres is their property. It does not belong to the Iraqi government. Evidence of the massacre that happened here has been destroyed. The building for sheep was demolished and put in a pile covered with dirt. The field of bones had been burned one year ago. Before leaving, I told the commander and his number two man about the men who had died there and the 28 females who had been captured by ISIS. They are the wives and children of brothers Barakat, Murad, and Mirza. Reports are that more than 47 people were shot on this farm.

I have talked to a number of Ezidis who have returned for a day to their empty houses in the villages. For them it is like going to a graveside to make one's final farewell. With great wailing, they pick up scraps of old school papers, or a broken crib or a stuffed bear spilling its insides, or the neck of their broken tambour stringed instrument. When asked if they think they can ever return, they all share one answer: "That would be hard."

Yezidis are facing a cruel choice to remain in tents for years or return to their destroyed villages. In the week I was traveling to every village on the south side of the mountain, I saw absolutely no rebuilding or repair activity, including no de-mining. In view of the bitter reality that no one is coming to their rescue with rebuilding funds or asylum, many are contemplating returning and risking another genocide. Their number one priority is to de-mine their villages and open the road from Faysh Khabour to Shingal.

I saw several thousand sheep in a dozen herds tended by shepherds dressed in traditional Arab clothing. These shepherds are Sunni Arabs from Baaj, which was a headquarters for ISIS when they attacked Shingal from the southwest. They are grazing their sheep on Yezidis' land. The Yezidis do not know them and worry that some might be ISIS. This is a quiet way to take control of the land of Shingal.

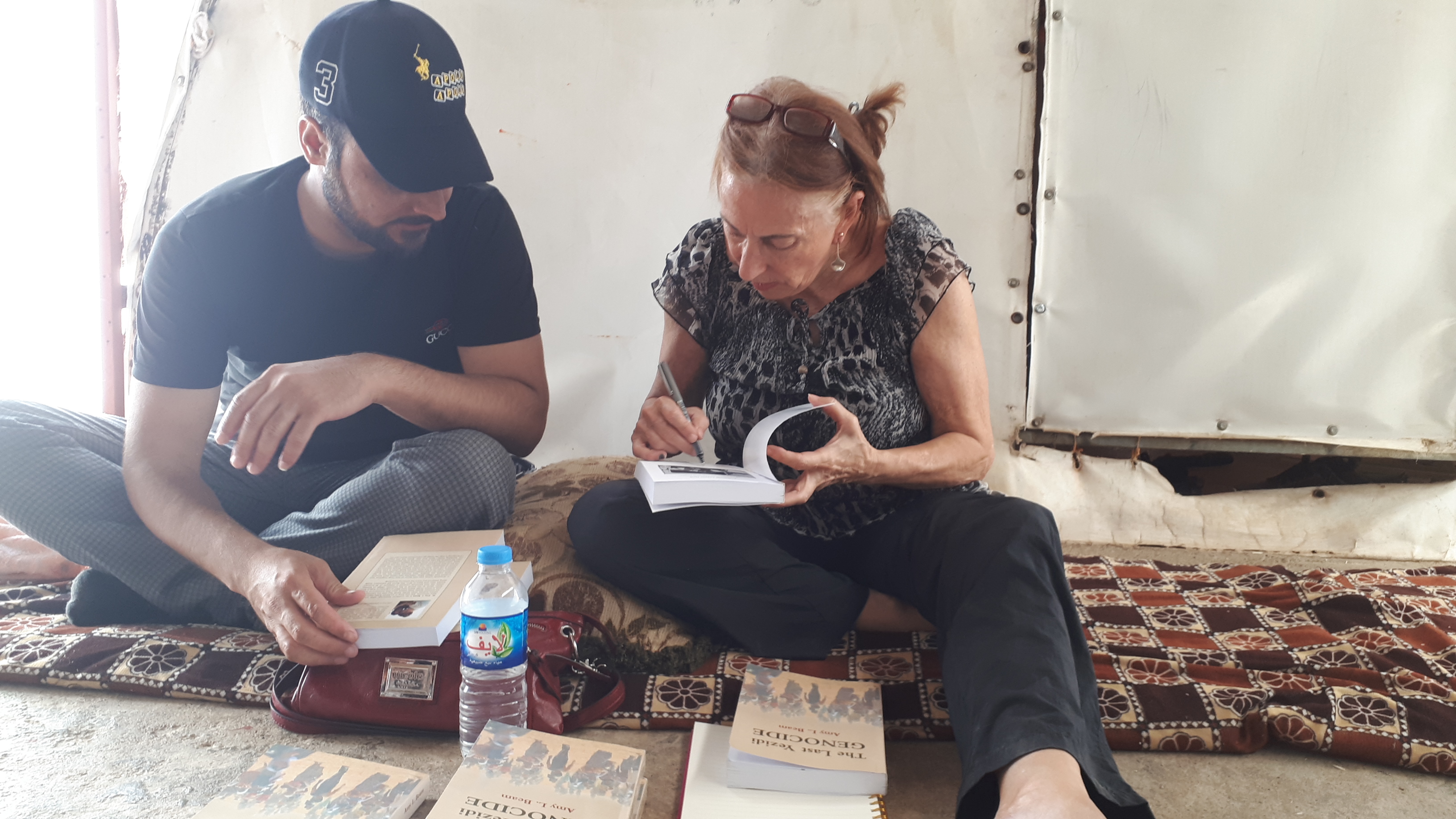

Dr. Amy L. Beam is the author of "The Last Yezidi Genocide." She reported this piece during a trip to the empty villages in Shingal May 21-28, 2018.

Rasho Ali Nemer in Snoni

Poles with no electric cables

Naim Ali Doors

Ayham and Anis Azad Alias

Amy Beam signing books

Amy Beam with Muna Qassim Muso and Hani Khairi Murad Pissee

Menjay Ali Yusef survivor

Damoa Falah Hassan and Amy Beam

Survivors Qadia

Bomb Pidqee Shamal

Khalid Murad Pissee

Sameh Pissee Taha Kocho survivor

Sinjar city house destroyed

Ali Abbas Ismail Loko's wound

Chicken coop destroyed in Solagh

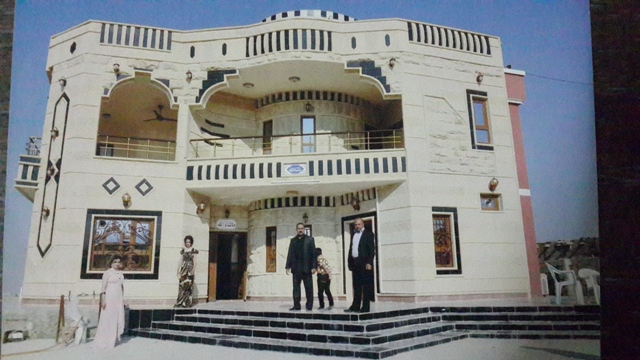

Hassan Alyias Hami’s house when first built in 2013

Hassan Alyias Hami’s house after being destroyed

Hazim Qassim Avdo from Kocho